NEW WORLD CHEF

On West Flagler Street in Miami, not far from Calle Ocho, the long street that’s the heartbeat of the city’s vibrant Cuban life, sits an open-air food stand called the Palacio de los Jugos. It began about 20 years ago as a juice bar–hence its name, the Palace of Juices–but has expanded over the years to serve Cuban specialties and offer the finest and freshest produce from the Caribbean and Central and South America. It is here on a crisp, sunny Florida day, amid scores of Cuban-American families sitting on wooden picnic benches and cheerfully and noisily dining alfresco, that Norman Van Aken, chef and co-owner of NORMAN’S in Coral Gables, Florida, has come in search of sapodillas, mamey sapotes, calabaza, tamarind, boniato, cherimoyas and plantains, some of the exotic fruits and vegetables that are a prime part of his acclaimed “New World” cuisine.

“This is a sapodilla,” Van Aken says. “When it ripens it has an unusual root-beer, maple-sugar kind of sweetness. Once, for a special dinner, I made a black-cow sundae and let the sapodilla be the flavor of the root beer.” He picks up another fruit. “These are cherimoyas. They’re native to Peru. Cherimoya means ‘cold stone.’ They’re found high in the Andes, where I’m sure the stones are very cold. I might use them in a savory chicken salad, with a Chinese marinade, and add avocado. What I do is analyze the flavor of the fruit or vegetable and decide what it makes me want to do with it.”

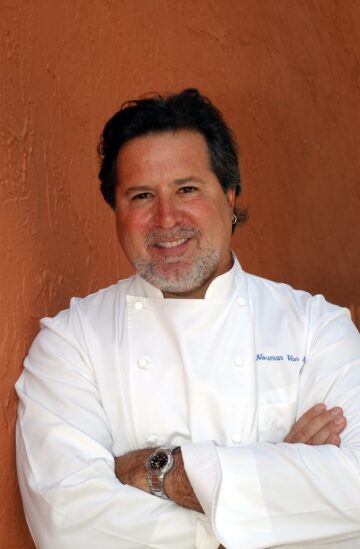

Van Aken has a face that makes him seem a decade or more younger than his 48 years. He is soft spoken, with a down-home, relaxed and friendly nature, an unfailingly natural smile and twinkling eyes. But in his voice is a precision that reveals the intensity, the expertise beneath the mellow surface.

He got his first cooking job in 1971, when he was 20 years old, slinging breakfast hash in an Illinois diner that had a giant faux milk jug on its roof. Today, after two decades of ups and downs, of early successes and frustrating failures, he is a highly recognized and much honored pioneer of a type of cooking he helped create: the fusion of Old World haute techniques and the tropical, tangy and intensely flavored ingredients of Florida, Cuba, the Caribbean and Latin America. It is a fusion he calls ‘New World Cuisine’.

In 1996, Van Aken won the Robert Mondavi Culinary Award of Excellence. A year later, he was the James Beard Foundation’s choice as best chef in the Southeast. He recently won the Food Arts Silver Spoon award for lifetime achievement from Cigar Aficionado’s sister publication. The New York Times has anointed NORMAN’S “the best restaurant in South Florida,” and the New York Daily News has called it “the best restaurant south of Paris.” For the past three years NORMAN’S has made the top three in ‘Gourmet’ magazine’s readers’ choice of the best restaurants in South Florida, twice finishing first. NORMAN’S made ‘Playboy’ magazine’s 1998 list of the top 25 restaurants in America, putting Van Aken in the company of such world-renowned chefs as Daniel Boulud and Charlie Trotter, a longtime friend.

Van Aken has appeared on CNN, “Good Morning America” and “CBS This Morning,” and is the official “Chef in the Sky” for all United Airlines Latin American and Caribbean flights. He is the best-known member of a group of Florida-based chefs–among them Alan Susser of Chef Allen’s in North Miami Beach, Mark Militello of Mark’s in Fort Lauderdale, and Douglas Rodriguez, recently of Patria in Manhattan–who put New World cuisine on the food map. He is the author of three critically praised cookbooks and is writing a fourth. His most recent, ‘Norman’s New World Cuisine’, was one of three finalists for the 1997 Julia Child “best chef-authored cookbook” award. Remarkably, Van Aken has made it to the top of his profession without spending a single day in cooking school. Through years of experience, reading, experimenting and learning, he has become a master chef.

“If I was going to do this for a living, I wanted to be very good at it,” says Van Aken, whom just about everyone calls Norman. “From the time I was eight years old I knew I wanted to be really good at something. I wanted to be involved with life. And I’m voraciously hungry in my spirit, so I think it’s perfect for me to be a chef.”

Many of his formative years as a chef were spent in Key West, Florida, and he considers himself very much a Key West kind of guy–he says he still thinks of himself as a former hippie, a survivor of the late 1960s and early ’70s, when he hitchhiked around the country, trying to find himself and to run away from the problems of home. His restaurant mirrors his personality: a light, friendly and relaxing place. The decor of NORMAN’S is appropriately multicultural–beamed ceilings, a tan, stucco, almost Mediterranean look to the walls and columns, Balinese wooden sculptures sharing wall space with an oil portrait of Van Aken. The restaurant, on a site where four previous restaurants failed, was put together on a small budget–less than $500,000. “The floor and the bar were made from the stone tabletops of the previous restaurant,” Van Aken says.

Toward the back of the room, a number of dishes are cooking on two wood-burning stoves. A recent $750,000 expansion has boosted the restaurant’s capacity to 235 seats. Because he is a lover of cigars, Van Aken made certain that the new section includes a bar where patrons can smoke cigars and sip Cognacs and other spirits. The diners are generally a happy, noisy crowd. A sense of joy and luxury pervades: diners are eager to see and be seen, and the food and atmosphere are equally savory. The patrons are a cross-section of southern Florida, Anglo and Latino, some in full Armani tie and jacket, others in casual shirt sleeves, the women in basic-black Prada or Donna Karan–or off-the-rack copies.

Under the supervison of Rob Boone, NORMAN’S chef de cuisine, as many as 18 chefs a night prepare the delicacies for 10,000 customers a year. Two hundred guests will dine on a busy off-season night and 350 at the height of the winter season, with projections of $5 million in business yearly now that the expansion is complete. Norman spends part of his evening strolling from table to table, greeting newcomers, kissing the cheeks of the regulars, shaking hands, ever the gracious host, smiling and discussing the menu, the weather, the family.

His restaurant manager/sommelier does the same, studiously attentive, always informative, answering questions, offering help with the wine list, wishing a happy birthday or anniversary, just chatting about the events of the day.

Behind it all is the food. For all great chefs the ingredients must be the finest, the freshest the region can offer. “It’s all about the region,” Van Aken says. “The multicultural southern tip of Florida–the nexus of North America and the Caribbean, touching Cuba, the Florida Keys, the Yucatan, the West Indies, the Bahamas and South America. The cuisines of the Old World merge with the foods of the New World.” It’s also about fusion–a term Van Aken is credited with being the first to use in connection with food–“the fusion that’s at the heart of New World cuisine. It’s what I know and what I love.” The multiculturalism includes a taste of Africa and Asia, Africa as a “logical and historical extension of the diaspora to the Caribbean,” Japanese as “a food esthetic I admire,” and Vietnamese as a kind of cooking “I just fell in love with.”

His methodology, he says, is based on the “north, east, south and west of flavors–sweet, sour, salt and bitter. The complexity of the flavors travels in different directions.”

The complexity is reflected in the menu. Here’s a sample of recent dishes: Pan-cooked Piedmontese beef strip steak with a Maytag Blue Cheese flan, cipolline onions, black trumpet mushrooms, shaved organic hazelnuts and red wine-port reduction. (“The beef is grown on a small farm in Ohio and we get it through Buckhead Beef in Atlanta,” Van Aken says.) Pan-roasted Gulf escolar (“It’s from the Gulf of Mexico, and it’s richer than tuna.”) with braised escarole, crispy cockscomb, pommes frittes and a sherry-shallot jus. Calypso spice-rubbed mofongo-stuffed and roasted dolphin on Yuca fries with black bean essence, mojo de cana and a carambola salsa. (“The classic mofongo is made with sweet plantains and pork. It’s very rich. We make a substitution,” he says with a laugh. “We use foie gras instead of pork.”) He also uses liver in his signature dish, down-island French toast with Curacao-scented and seared foie gras, griddled brioche, savory passion-fruit caramel, turmeric and gingery candied lime zest.

How did Van Aken learn to create those imaginative dishes? His immediate answer is deceptively simple. “Something in me intuitively knew what to do, in terms of cooking, in terms of flavors, in terms of adding the right ingredients. I seemed to know what would work. It’s difficult to describe. A lot happens simultaneously, a lot of data that sits in your mind from everything you’ve read and everything you’ve tasted, all the markets you’ve been to, what you’ve smelled, what you’ve cooked. Many people believe that what happens is you think of something for the first time that day. But there’s so much more. Thankfully, I’ve got a good memory.

“It’s a matter of going to a market and seeing what’s there–the market experience is really important to me. I keep charts in the kitchen for me and my chefs to see what’s in season every month. I know that early in November, for the first time sea scallops will be coming in. It’s a matter of working with the seasons. A lot has to do with a balance between acidity and meatiness–whether it’s meat, fish or chicken, or even vegetables that have a sort of meaty quality–and with manufacturing textures, crunchiness and softness. It’s a question of how are you going to create this fulcrum, this balancing beam, this teeter-totter–but it’s not only linear, it becomes multidimensional, with curlicues, circles, Ferris wheels of flavors and opportunities.”

For Van Aken, that basic intuition was developed through decades of experience. His mother was in the restaurant business–rising from waitress to hostess to cashier to assistant manager and eventually to manager. “And my great-great-great grandmother was the baker for the queen of England when the queen had her summer residency in Scotland,” he says. “So the culture of a restaurant was something in the fabric of my life. There was an air of concern for food. We would make our own tomato preserves and things like that. We had a neighbor we called Grandpa Ray who had a huge garden, and we would wander it with him.”

The prime fabric of his early life, however, was the troubled marriage between his parents, who separated when he was 10 and divorced when he was 16. (He has two sisters.) “It was–how would you put it–a very bumpy childhood,” he says. “Much of my early life until my father died [when Van Aken was 17] was about them and their breakups with each other. Actually, I think that cooking helped me overcome a lot of it. I really think I needed to be in an artistic sort of business. Artists try to remake the world. I try to make it a creative place I can have fun with and control–a peaceful, positive place. A little raucousness is good, but ultimately I wanted to be able to make peace with people.”

After graduating from high school, Van Aken tried his hand at college–first at Northern Illinois University, then in Hawaii–but he soon decided college was not for him. “I loved learning and reading, but somehow or other school didn’t fit with my nature,” he says. “So I started to work lots of different jobs, whatever came along. I worked construction, factories, I painted houses, sold flowers on the street in Honolulu. I hitchhiked around a lot. I was reading, writing–mostly songs and short stories, lyrics for the bands of the guys I was hanging around with. It was a very early-’70s kind of thing.”

In 1971, a friend suggested they go to Key West. He stayed a month, then returned to Illinois, where he got a job cooking in the Libertyville diner, the one with that milk jug on top. “Earlier in my life I had been a bus boy and a dishwasher,” he says. “My mom was managing restaurants, and she pulled me into them.”

At the diner, he met a waitress named Janet, who would become his wife and recipe tester. They’ve been together for more than 25 years, married since 1976, and have a son, Justin, 19, a college student in South Florida. But Van Aken was soon drawn back to the Keys. “Key West really fit my soul,” he says. “It was the place for me–a renegade place, but a gentle renegade. It was raffish, comfortable. I was a student of the Beats, reading all about them, and Key West fit right in.”

It was in Key West that, over more than a decade, Van Aken began “to accept and then fall in love with the idea of being a chef. For a long time, though, I was a cook, not a chef.” He recalls the moment of change. “I had been cooking from 1971 to ’79, and I applied for a job at the Pier House. They said I should come in and see the chef, so I walked in and she was in the middle of tasting a dessert to be served that night. She took a taste and looked at the pastry chef and didn’t say anything–she just threw it right in the garbage, plate and all. And then she said, ‘You can’t be serious. We’ll never serve anything like that in this restaurant.’ And I mean, I had worked in places back in Illinois where you had to get a guy off a barstool just to come over and do the dishes. So I applied for the job and got it. The restaurant was hiring the first graduates from the Culinary Institute of America, and suddenly I was around people who cared about food.

“I was a sous-chef, and one of the chefs I was working for used a term–“veal velouté” — and I said, ‘How do you know that term?’ And he said, ‘Because I went to culinary school.’ He’s leaning on a mixer, and he says, ‘Why don’t you go to school?’ And I said, ‘It costs like $20,000, right? You know I don’t have that kind of money.’ So he said, ‘Why don’t you read?’ And I was stung. I said, ‘What do you mean? I read.’ And he said, ‘Why don’t you read cookbooks?’ I looked at him, and on the way home I stopped off at a bookstore and picked up James Beard’s ‘Theory and Practice of Good Cooking’. I still have it. And that’s when I started to read.”

As he read, he would prepare recipes. “I started on a second-hand wooden table in our rented house in Key West,” he says. “I would read book after book after book. When I wasn’t at work cooking I was at home reading. I had one French knife. I’d wrap it in a towel, ride my bicycle to work, work my butt off, come home, read magazines like ‘Gourmet’ and underline many passages. I would cook on Sunday or whatever my day off would be.”

Among the most influential books for him, he says, were Alice Waters’ ‘Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook’ and books by Roger Vergé of Le Moulin de Mougins on the French Riviera and Alain Senderens of Lucas-Carton in Paris. “In terms of the French chefs, I especially liked Senderens and Vergé because they were willing to cross-culturalize their food a bit more than some of the more rigid chefs. And there was a book called ‘The Great Chefs of France’, chefs of 12 Michelin three-star restaurants. I read it again and again. I stared at every picture. I underlined it, made notes in the margins and dreamed of creating a model like theirs, but with an American spirit. Books were a very important aspect of the road I took.

“I’d be reading how to make this foamy sabayon [an egg-and-wine mixture] that the Troisgros brothers were creating for their fish in Roanne, France, and I would have my French knife on top of the book and I would be making the sauce with some local yellowtail snapper in Key West and not having anybody to talk to about how to make it. There was no famous chef. There was no school. If it didn’t work I had to do it over again. But instinctively I pretty much knew what to do. I understood a lot of things about acidity and how it helped relieve the richness of some of the food. I also tried to differentiate my cuisine a little bit by studying whatever Spanish, Caribbean or Portuguese things I could find.”

He would talk to the locals a lot. “I’d go to the little cafés in Key West. I’d sit on a stool by the counter, not knowing much Spanish, asking, ‘What’s this, why is it called this?’ I asked the people sitting next to me–the post office guy, the cop, the waitress–and eventually I began to integrate these things into what I was doing.”

He would go from restaurant to restaurant–he worked at Pier House, Port of Call, Chez Nancy–reading and learning and doing. “Every ring became tighter and faster and stronger,” he says. “I began to find this life force, I really began to know what I wanted to do. In Key West, it was like the boats are right here, the fish is right here. I’m cooking for people who are writing novels and doing all kinds of creative things, people like Tennessee Williams and Leonard Bernstein. And I began to get smatterings of recognition, just enough to feed my spirit and my mind.”

A year after their son’s birth in 1980, Norman and Janet decided to return to Illinois, where Norman eventually got a job as executive chef for the restaurateur Gordon Sinclair at Sinclair’s in Lake Forest. But even back home, he remained true to his newfound roots. “I’m in Illinois, and I’m cooking what I know–things like Bahamian conch chowder. The critics wrote about this guy with a passion for Hemingway-like flavors, the Key West connection. I was doing black beans and conch. That was my first national press, and I thought that if they like that, they like what I like–and I was very glad they liked it.”

At Sinclair’s, Van Aken met someone who would become a lifelong friend. “There was a guy working in the dining room as a busboy, and he asked for a job in the kitchen,” he recalls. “He was this skinny little northern Illinois guy, wearing a white shirt that was a little too big for him, and my sous-chef said, ‘Come on, let’s give him a chance.’ So we did.”The skinny guy’s name was Charlie Trotter, now owner of Charlie Trotter’s in Chicago and, like Van Aken, one of the top chefs in the country.

Van Aken’s next job was also for Sinclair, at the Jupiter (Florida) Hilton. But the lure of Key West remained strong, and in 1985 he and his family moved back. Van Aken was hired as chef at the renowned, and reopened, Louie’s Backyard, which had been closed for seven years but had once been the haunt of Truman Capote, Jimmy Buffett and Peter Fonda. Norman’s reputation continued to grow–and it was at Louie’s that he had his haute cuisine epiphany.

“I began to look at the regional food movement, with Jeremiah Tower and Alice Waters in California, and in the American Southwest, and at first I sort of sprang out of my seat and thought, I need to move to California, to the wine country, and be part of it,” he says. “But then I realized that I like it here, and our son, Justin, is going to school here, and we live here and have friends here. So I began to think that maybe I should try to do with Florida what those other chefs did with California and the Southwest and try to create an appreciation for the sense of place here in South Florida.”

Then he wrote an article about something he called “Fusion.” “I’m the first chef ever to have used that term, that’s been established,” he says. “I was asked to go to Santa Fe and give a speech, and just precedent to the time I was reading a book by the French historian Jean-François Ravel called ‘On Culture and Cuisine’ and I was having this internal argument. I knew how to cook some French dishes and some Italian dishes, some Bahamian dishes and some Cajun dishes. But I thought, this is bullshit. I’m cooking everybody else’s stuff. I’ve got to find my own voice. So I decided I was going to try to make sense of Florida, to find a way to make people come and experience Florida — celebrating and fusing Cuban, Bahamian, Haitian and the American South.”

In 1987, Louie’s Backyard and Van Aken’s cooking were featured in an article in Bon Appetit magazine. Subsequently, an executive at Ballantine Books who had eaten at the restaurant but whom Van Aken had never met called and asked him to write a cookbook. The book, ‘Feast of Sunlight’, was another step on the chef’s road to the New World. Finally, in 1987, Van Aken decided he would open his own restaurant with his colleague and friend, Proal Perry. They called it MIRA. It had 38 seats, it was a critical success–and it closed after 18 months. “Business was a whole different thing from art,” he says. “I didn’t have any money. We thought we would open a super-elegant restaurant. It was a good idea but it was the wrong place to do it. There was no year-round residential population to support it. That was a real tough time, a real tough spot. I didn’t think that something like that could happen. But I’ve been through enough knocks in my life to know it’s not always going to be one towering moment after another.”

A few years later, Van Aken was hired as the executive chef at a new restaurant in Boca Raton, ‘Hoexter’s’, which was another disaster. “I went from 38 seats at Mira to 200 seats at Hoexters. Mira would do 50 or 60 dinners on a busy night. Hoexters would do 600. And Boca is a very different place from Key West.”

Not long after Hoexter’s, however, came “a Mano”, (it means ‘by hand’ in Spanish), in Miami Beach, which soon was heralded as the place to eat, attracting celebrities, models, rapturous food critics and a media blitz. “a Mano” became a major part of the South Beach scene, and Van Aken became a name to reckon with. But he was a chef, not an owner; the earlier failures had put him in a financial hole, and while he had achieved recognition, it had not come with money. His real goal, another restaurant of his own, was still beyond reach.

“But through it all you adapt, you struggle, you suffer, you draw on everything you need to keep it together,” he says. Finally, he got a group of investors together to open NORMAN’S in 1995–and the past four years have been a culmination, an entrance into chef’s paradise, with the full national and media attention he has so long desired.

These days, a typical 24 hours in Van Aken’s life are more than a little busy–but then they are also just what he wants. He, Janet and Justin live in Pinecrest, a residential area south of Coral Gables. “I’m up just before 7 a.m.,” he says. “I’ll make some tea, read the paper. Then I’ll organize some of the recipe work for my next cookbook. Janet gets up, and part of her day is spent testing recipes for the new book.”

Then Norman gets into his car–a silver BMW Z-3 convertible, his one ostentation–“I used to ride a motorcycle to work, but I would get soaked when it rained”–and it’s off to the gym, one hour a day, five or six days a week, with his personal trainer. Back home at about 11, he checks with Janet on how the recipes are coming: “If she thinks something has too much fat, or if the cooking time is too long, or the ingredient list is too overwhelming.” He has something light to eat, his first food of the day–“I try to eat interesting and healthy,” he says. And then it’s off to the restaurant. “First I’ll call to see if everything is flowing. It almost always is.”

He arrives at about 11:30, a little later if he has first stopped at a market. “We’ll have a meeting upstairs with the waiters before lunch, I’ll check e-mail, I’ll work on the book, and I’ll focus on that evening’s menu,” he says. “About 2:30, when lunch is over, we go over what we’ll be serving that night for the tasting menu, what specials are coming in. My chef de cuisine, Rob Boone, and the pastry chef, Sam Gottlieb, may have questions, may want me to sample things. Once a week, we have a management meeting to go through everything that needs going through. At 5:15, the entire staff meets to discuss which guests are coming that night, if there are any regulars, and the sorts of dishes those regulars usually want.”

At 5:50, the dining room is checked to make sure “everything is beautiful, everything is just right.” Service starts at 6, but Norman will head back to his office for some final paperwork before entering the dining room between 6:30 and 7, as things begin to pick up. The rest of the evening is spent there and in the kitchen, socializing with the patrons, making sure everything is going as smoothly as can be–and helping out if it is not. “I don’t work on the line these days, as I did the first years,” he says. “People used to come in and ask for Norman, and they would be told, ‘He’s right there, cooking.'” This all continues until 11 or so. “I try now to wrap things up and get out of here so I’m back in bed about midnight,” he says. “It’s a full day. But we’re closed Sundays.”

When it is time to relax, on those Sundays and late at night after a hard day in the kitchen, one of Van Aken’s passions–and pleasures–is a good cigar. His favorite smoke reflects his loyalty to Miami and its Cuban ambiance. “My normal cigar is a local one, La Gloria Cubana,” he says. “I just think there are so many fake Cuban cigars out there that I’ve already been through, that unless I’m traveling abroad and can get real Cubans I generally don’t bother with them.”

The Cubans he prefers, when he can get them, are Romeo y Julieta, Bolivar and Punch, but most of the time he’ll stick with La Gloria Cubana. He prefers the robusto, La Gloria Cubana Wavell. “Usually I don’t have the time for a larger cigar.

He began smoking cigars about five years ago. “Like many things I’ve experienced in my life, whether it’s food or wine or cigars, I tend to like the best things. I like quality. I don’t mind having fewer things, so long as what I have is the tops. That’s why I got the BMW, and that’s why I like a good cigar. It’s not so I can show off to my buddies what I drink or smoke or drive.”

Sitting with a good cigar, he says, is very relaxing. “I like the fact that they help me slow down and observe, because I’m in a frenetic business. Smoking is dreamy. With a cigar I can listen to a song and really get into it, really get it, not just rush through it. I try to find the time. I rarely smoke a cigar unless I have the ability to sit down and enjoy it. I don’t take six hits and put it out and relight it. That’s awful. Sometimes I try to leave the restaurant a little earlier and go home. We live on a canal and there’s a pool in the backyard, and I go out there and light up and look at the stars and think about life. And what I want to cook tomorrow.”

Tomorrow for Van Aken is full of opportunity, but for him that opportunity means staying in Florida and concentrating on his restaurant. “I’ve thought about the future a lot,” he says. “And I’ve realized that what I really love about what I do is cooking. I love making plates. I could open four restaurants and travel between them, but that’s not what makes me tick. What makes me tick is working over a plate, writing the menus, working with the people I love working with. I enjoy the physical activity, I enjoy the artistic side. I like the heart-pounding feeling at 4 in the afternoon when you suddenly realize you’ve got to get things ready. I enjoy the way you feel drained at 11:30 at night after a successful evening. It’s a good, hard run. I love the creativity I feel when I change my mind in the middle of a tasting menu and decide to serve something else to fit the new wine a table has ordered. I love the language of menus.

“Yes, I’m working with airlines, I’m writing my fourth book, I’m hoping to do a television program, all this other stuff. But what I like is the connection between me and the guest through the plate. Yes, I could have a business that took in $15 million a year. But how much money do you need? I need more than I’ve got, that’s for sure. But what I mostly need is to feel good about my life. I guess deep down inside, I’m still a bit of a hippie.”

But most of all, he has found a home. “It’s nice to see that our region is being recognized. And I’m really delighted that I’m the one people think of first when they think about Florida and food. I want this restaurant to be known around the world. I want this place to be on the short list of where to eat in America. I want Norman’s to be the place to go when people want to experience Florida. I don’t want it to be known as ultra-fancy or exclusive, because that’s not what my personality is about. I’d also like to be known as a great teacher. I’d like to offer classes to help economically disadvantaged people who want to be students of fine cuisine.”

It would be, he says, a kind of ‘Norman University’. But for Van Aken himself, that university is life, and he shows no signs of stopping. “What I’ve known about cuisine for a long, long time is that the study of it is bottomless,” he says. “I’ll be able to learn when I’m 80 years old.” And his customers will be the ones to benefit.

Mervyn Rothstein is an editor at The New York Times and a frequent contributor to Cigar Aficionado. Article appeared originally in January/February issue, 2000. This article has been slightly edited for length and clarity.